Descrizione

PREMESSA: LA SUPERIORITA’ DELLA MUSICA SU VINILE E’ ANCOR OGGI SANCITA, NOTORIA ED EVIDENTE. NON TANTO DA UN PUNTO DI VISTA DI RESA, QUALITA’ E PULIZIA DEL SUONO, TANTOMENO DA QUELLO DEL RIMPIANTO RETROSPETTIVO E NOSTALGICO , MA SOPRATTUTTO DA QUELLO PIU’ PALPABILE ED INOPPUGNABILE DELL’ ESSENZA, DELL’ ANIMA E DELLA SUBLIMAZIONE CREATIVA. IL DISCO IN VINILE HA PULSAZIONE ARTISTICA, PASSIONE ARMONICA E SPLENDORE GRAFICO , E’ PIACEVOLE DA OSSERVARE E DA TENERE IN MANO, RISPLENDE, PROFUMA E VIBRA DI VITA, DI EMOZIONE E DI SENSIBILITA’. E’ TUTTO QUELLO CHE NON E’ E NON POTRA’ MAI ESSERE IL CD, CHE AL CONTRARIO E’ SOLO UN OGGETTO MERAMENTE COMMERCIALE, POVERO, ARIDO, CINICO, STERILE ED ORWELLIANO, UNA DEGENERAZIONE INDUSTRIALE SCHIZOFRENICA E NECROFILA, LA DESOLANTE SOLUZIONE FINALE DELL’ AVIDITA’ DEL MERCATO E DELL’ ARROGANZA DEI DISCOGRAFICI .

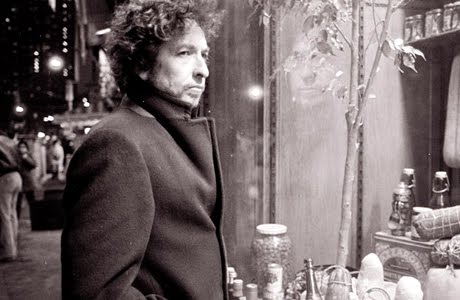

BOB DYLAN

empire burlesque

Disco LP 33 giri , CBS records , CBS 86313 , 1985, nederland / europe

ECCELLENTI CONDIZIONI, vinyl ex++/NM , cover ex++/NM

Empire Burlesque è il ventitreesimo album in studio del cantautore Bob Dylan, pubblicato dalla Columbia Records nel giugno 1985.

Le tecniche di produzione utilizzate per Empire Burlesque sono quelle più tipicamente artificiali, sintetiche ed infami degli anni ottanta, quando l’ ormai ex menestrello prodigio veniva dilaniato da frequenti travasi di bile assistendo furioso ed impotente allo scalaggio delle classifiche da parte di gentaglia come Duran Dura, Spandau Ballet, Madonna e George Michael, tutti quanti artisticamente delle vere e proprie cisti e per giunta molto più giovani e pimpanti di lui. Grazie all’ irriducibile zoccolo duro dei vecchi inguaribili fans – molti dei quali nel frattempo erano diventati pure sordi e senza alcuna speranza di guarigione – raggiunse perlomeno la posizione numero 33 negli Stati uniti e la numero 11 nel Regno Unito.

Etichetta: Cbs Records

Catalogo: CBS 86313

Data di pubblicazione: 1985

- Supporto:vinile 33 giri

- Tipo audio: stereo

- Dimensioni: 30 cm.

- Facciate: 2

- Red label, lyrics and picture inner sleeve

Track listing

All songs by Bob Dylan.

Side A

- Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love) – 5:19

- Seeing the Real You at Last – 4:18

- I’ll Remember You – 4:12

- Clean Cut Kid – 4:14

- Never Gonna Be the Same Again – 3:06

Side B

- Trust Yourself – 3:26

- Emotionally Yours – 4:36

- When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky – 7:18

- Something’s Burning, Baby – 4:51

- Dark Eyes – 5:04

Musicians

- Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar (A2, A4, B1, B3 and B5), keyboards (A1 and A5), piano (A3 and B2), harmonica (B5)

- Peggie Blu – backing vocals (A1, A4 and A5)

- Debra Byrd – backing vocals (A5 and B1)

- Mike Campbell – guitar (A2, A3, B1 and B2)

- Chops – horns (A2)

- Alan Clark – synthesizer (A5)

- Carolyn Dennis – backing vocals (A1, A4, A5 and B1)

- Sly Dunbar – drums (A1, A5 and B3)

- Howie Epstein – bass guitar (A3 and B2)

- Anton Fig – drums (A4)

- Bob Glaub – bass guitar (A2)

- Don Heffington – drums (A2 and B4)

- Ira Ingber – guitar (B4)

- Bashiri Johnson – percussion (A2, B1 and B3)

- Jim Keltner – drums (A3, B1 and B2)

- Stuart Kimball – electric guitar (B3)

- Al Kooper – rhythm guitar (B3)

- Queen Esther Marrow – backing vocals (A1, A4, A5 and B1)

- Sid McGinnis – guitar (A5)

- Vince Melamed – synthesizer (B4)

- John Paris – bass guitar (A4)

- Ted Perlman – guitar (A1)

- Madelyn Quebec – vocals (A3, B1, B3 and B4)

- Richard Scher – synthesizer (1, 5, 8 and 9), synth horns (7)

- Mick Taylor – guitar (A1)

- Robbie Shakespeare – bass guitar (A1, A5, B1, B3 and B4)

- Benmont Tench – keyboards (A2 and B1), piano (A4), organ (B2)

- Urban Blight – horns (B3)

- David Watson – saxophone (A2)

- Ronnie Wood – guitar (A4)

- Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar (A2, A4, B1, B3 and B5), keyboards (A1 and A5), piano (A3 and B2), harmonica (B5)

- Peggie Blu – backing vocals (A1, A4 and A5)

- Debra Byrd – backing vocals (A5 and B1)

- Mike Campbell – guitar (A2, A3, B1 and B2)

- Chops – horns (A2)

- Alan Clark – synthesizer (A5)

- Carolyn Dennis – backing vocals (A1, A4, A5 and B1)

- Sly Dunbar – drums (A1, A5 and B3)

- Howie Epstein – bass guitar (A3 and B2)

- Anton Fig – drums (A4)

- Bob Glaub – bass guitar (A2)

- Don Heffington – drums (A2 and B4)

- Ira Ingber – guitar (B4)

- Bashiri Johnson – percussion (A2, B1 and B3)

- Jim Keltner – drums (A3, B1 and B2)

- Stuart Kimball – electric guitar (B3)

- Al Kooper – rhythm guitar (B3)

- Queen Esther Marrow – backing vocals (A1, A4, A5 and B1)

- Sid McGinnis – guitar (A5)

- Vince Melamed – synthesizer (B4)

- John Paris – bass guitar (A4)

- Ted Perlman – guitar (A1)

- Madelyn Quebec – vocals (A3, B1, B3 and B4)

- Richard Scher – synthesizer (1, 5, 8 and 9), synth horns (7)

- Mick Taylor – guitar (A1)

- Robbie Shakespeare – bass guitar (A1, A5, B1, B3 and B4)

- Benmont Tench – keyboards (A2 and B1), piano (A4), organ (B2)

- Urban Blight – horns (B3)

- David Watson – saxophone (A2)

- Ronnie Wood – guitar (A4)

The opening track, “Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love)“, was originally recorded for 1983’s Infidels under the title “Someone’s Got a Hold of My Heart” (eventually released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991). It was re-written and re-recorded several times before finding its way on to Empire Burlesque. A lushly produced pop song riding a reggae groove courtesy of Robbie Shakespeare and Sly Dunbar (better known as Sly & Robbie), the love song was singled out as the best track on the album by the most recent edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide. The track, which features Mick Taylor on guitar (from Dylan’s 84 Tour), was also chosen as the first single for Empire Burlesque.

Clinton Heylin describes “Seeing the Real You at Last” as “a compendium of images half remembered from Hollywood movies,” as many of the lyrics made “allusions to Humphrey Bogart movies, Shane, even Clint Eastwood‘s Bronco Billy.”

The love ballad, “I’ll Remember You” was still played in concert until 2005, more so than all but one other song from Empire Burlesque. It was also featured, in an acoustic version, in the movie Masked & Anonymous, though not included on the released soundtrack.

“Clean-Cut Kid” was another song recorded during the Infidels sessions. The lyrics weren’t finished until much later, and the finished result was included on Empire Burlesque. In the interim Bob gave the song to Carla Olson of the Textones as a thank you for her appearing in his first-ever video, Sweetheart Like You. She included it on the Textones’ debut album Midnight Mission and Ry Cooder was featured on slide guitar. A novelty song wrapped around sharp political commentary, the ‘clean-cut kid’ is an average American kid who’s radically altered by his experience in the Vietnam War. Village Voice critic Robert Christgau praised it as “the toughest Vietnam-vet song yet.”

When members of the press, as well as Dylan’s own fans, dubbed Empire Burlesque as ‘Disco Dylan,’ it was mainly for the song “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky.” An evocative song filled with apocalyptic imagery, it was originally an upbeat, piledriving rocker recorded with Steven Van Zandt and Roy Bittan, both members of Bruce Springsteen‘s E Street Band. Unsatisfied with the recording, Dylan and Baker radically recast the song as a contemporary dance track. (The earlier version was later released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991.)

The penultimate song, “Something’s Burning, Baby”, is another song filled with apocalyptic imagery. A slow-building march accented with synthesizers, it was singled out by biographer Clinton Heylin as the strongest track on Empire Burlesque: “An ominous tale set to a slow march beat, [it] was a welcome reminder of his ongoing preoccupations with that dreadful day.”

“Dark Eyes” features only Dylan on guitar and harmonica. According to earlier interviews and Dylan’s autobiography, Chronicles, it was written virtually on demand when Arthur Baker suggested something simpler for the album’s final track. Dylan liked the idea of closing the album with a stark, acoustic track, particularly when the rest of the album was so heavily produced. However, Dylan didn’t have an appropriate song. He returned to his hotel in Manhattan after midnight, and according to Dylan:

“As I stepped out of the elevator, a call girl was coming toward me in the hallway—pale yellow hair wearing a fox coat—high heeled shoes that could pierce your heart. She had blue circles around her eyes, black eyeliner, dark eyes. She looked like she’d been beaten up and was afraid that she’d get beat up again. In her hand, crimson purple wine in a glass. ‘I’m just dying for a drink,’ she said as she passed me in the hall. She had a beautifulness, but not for this kind of world.”

The brief, chance encounter inspired Dylan to write “Dark Eyes,” which was quickly recorded without any studio embellishment. Structured like a children’s song, with very rudimentary guitar work and very simple notes, it’s often quoted for its last chorus: “A million faces at my feet, but all I see are dark eyes.”

A number of critics have noted the bizarre sources of inspiration behind some of the songs. As mentioned, some lines were lifted from old Humphrey Bogart pictures, but at least a few were taken from the sci-fi television show, Star Trek. Author Clinton Heylin wrote that “one of the best couplets—”I’ll go along with the charade / Until I can think my way out’ (from “Tight Connection to My Heart”)—actually comes verbatim from a Star Trek episode, ‘Squire of Gothos’.” Some then say this line was originally used in the Humphrey Bogart movie Sahara, but it was not.

Bob Dylan’s influence on popular music is incalculable. As a

songwriter, he pioneered several different schools of pop songwriting,

from confessional singer/songwriter to winding, hallucinatory,

stream-of-conscious narratives. As a vocalist, he broke down the

notions that in order to perform, a singer had to have a conventionally

good voice, thereby redefining the role of vocalist in popular music.

As a musician, he sparked several genres of pop music, including

electrified folk-rock and country-rock. And that just touches on the

tip of his achievements. Dylan’s force was evident during his height of

popularity in the ’60s — the Beatles’ shift toward introspective

songwriting in the mid-’60s never would have happened without him —

but his influence echoed throughout several subsequent generations.

Many of his songs became popular standards, and his best albums were

undisputed classics of the rock roll canon. Dylan’s influence

throughout folk music was equally powerful, and he marks a pivotal

turning point in its 20th century evolution, signifying when the genre

moved away from traditional songs and toward personal songwriting. Even

when his sales declined in the ’80s and ’90s, Dylan’s presence was

calculable.

For a figure of such substantial influence, Dylan

came from humble beginnings. Born in Duluth, MN, Bob Dylan (b. Robert

Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) was raised in Hibbing, MN, from the age

of six. As a child he learned how to play guitar and harmonica, forming

a rock roll band called the Golden Chords when he was in high school.

Following his graduation in 1959, he began studying art at the

University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. While at college, he began

performing folk songs at coffeehouses under the name Bob Dylan, taking

his last name from the poet Dylan Thomas. Already inspired by Hank

Williams and Woody Guthrie, Dylan began listening to blues while at

college, and the genre weaved its way into his music. Dylan spent the

summer of 1960 in Denver, where he met bluesman Jesse Fuller, the

inspiration behind the songwriter’s signature harmonica rack and

guitar. By the time he returned to Minneapolis in the fall, he had

grown substantially as a performer and was determined to become a

professional musician.

Dylan made his way to New York City in

January of 1961, immediately making a substantial impression on the

folk community of Greenwich Village. He began visiting his idol Guthrie

in the hospital, where he was slowly dying from Huntington’s chorea.

Dylan also began performing in coffeehouses, and his rough charisma won

him a significant following. In April, he opened for John Lee Hooker at

~Gerde’s Folk City. Five months later, Dylan performed another concert

at the venue, which was reviewed positively by Robert Shelton in the

-New

York Times. Columbia AR man John Hammond sought out Dylan on the

strength of the review, and signed the songwriter in the fall of 1961.

Hammond produced Dylan’s eponymous debut album (released in March

1962), a collection of folk and blues standards that boasted only two

original songs. Over the course of 1962, Dylan began to write a large

batch of original songs, many of which were political protest songs in

the vein of his Greenwich contemporaries. These songs were showcased on

his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Before its release,

Freewheelin’ went through several incarnations. Dylan had recorded a

rock roll single, “Mixed Up Confusion,” at the end of 1962, but his

manager, Albert Grossman, made sure the record was deleted because he

wanted to present Dylan as an acoustic folky. Similarly, several tracks

with a full backing band that were recorded for Freewheelin’ were

scrapped before the album’s release. Furthermore, several tracks

recorded for the album — including “Talking John Birch Society Blues”

— were eliminated from the album before its release.

Comprised

entirely of original songs, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan made a huge

impact in the U.S. folk community, and many performers began covering

songs from the album. Of these, the most significant were Peter, Paul

Mary, who made “Blowin’ in the Wind” into a huge pop hit in the summer

of 1963 and thereby made Bob Dylan into a recognizable household name.

On the strength of Peter, Paul Mary’s cover and his opening gigs for

popular folky Joan Baez, Freewheelin’ became a hit in the fall of 1963,

climbing to number 23 on the charts. By that point, Baez and Dylan had

become romantically involved, and she was beginning to record his songs

frequently. Dylan was writing just as fast, and was performing hundreds

of concerts a year.

By the time The Times They Are A-Changin’

was released in early 1964, Dylan’s songwriting had developed far

beyond that of his New York peers. Heavily inspired by poets like

Arthur Rimbaud and John Keats, his writing took on a more literate and

evocative quality. Around the same time, he began to expand his musical

boundaries, adding more blues and RB influences to his songs. Released

in the summer of 1964, Another Side of Bob Dylan made these changes

evident. However, Dylan was moving faster than his records could

indicate. By the end of 1964, he had ended his romantic relationship

with Baez and had begun dating a former model named Sara Lowndes, whom

he subsequently married. Simultaneously, he gave the Byrds “Mr.

Tambourine Man” to record for their debut album. the Byrds gave the

song a ringing, electric arrangement, but by the time the single became

a hit, Dylan was already exploring his own brand of folk-rock. Inspired

by the British Invasion, particularly the Animals’ version of “House of

the Rising Sun,” Dylan recorded a set of original songs backed by a

loud rock roll band for his next album. While Bringing It All Back Home

(March 1965) still had a side of acoustic material, it made clear that

Dylan had turned his back on folk music. For the folk audience, the

true breaking point arrived a few months after the album’s release,

when he played ~the Newport Folk Festival supported by the Paul

Butterfield Blues Band. The audience greeted him with vicious derision,

but he had already been accepted by the growing rock roll community.

Dylan’s spring tour of Britain was the basis for D.A. Pennebaker’s

documentary Don’t Look Back, a film that captures the songwriter’s edgy

charisma and charm.

Dylan made his breakthrough to the pop

audience in the summer of 1965, when “Like a Rolling Stone” became a

number two hit. Driven by a circular organ riff and a steady beat, the

six-minute single broke the barrier of the three-minute pop single.

Dylan became the subject of innumerable articles, and his lyrics became

the subject of literary analyses across the U.S. and U.K. Well over 100

artists covered his songs between 1964 and 1966; the Byrds and the

Turtles, in particular, had big hits with his compositions. Highway 61

Revisited, his first full-fledged rock roll album, became a Top Ten hit

shortly after its summer 1965 release. “Positively 4th Street” and

“Rainy Day Women 12 35” became Top Ten hits in the fall of 1965 and

spring of 1966, respectively. Following the May 1966 release of the

double-album Blonde on Blonde, he had sold over ten million records

around the world.

During the fall of 1965, Dylan hired the Hawks,

formerly Ronnie Hawkins’ backing group, as his touring band. the Hawks,

who changed their name to the Band in 1968, would become Dylan’s most

famous backing band, primarily because of their intuitive chemistry and

“wild, thin mercury sound,” but also because of their British tour in

the spring of 1966. The tour was the first time Britain had heard the

electric Dylan, and their reaction was disagreeable and violent. At the

tour’s Royal Albert Hall concert, generally acknowledged to have

occurred in Manchester, an audience member called Dylan “Judas,”

inspiring a positively vicious version of “Like a Rolling Stone” from

the Band. The performance was immortalized on countless bootleg albums

(an official release finally surfaced in 1998), and it indicates the

intensity of Dylan in the middle of 1966. He had assumed control of

Pennebaker’s second Dylan documentary, Eat the Document, and was under

deadline to complete his book -Tarantula, as well as record a new

record. Following the British tour, he returned to America.

On

July 29, 1966, he was injured in a motorcycle accident outside of his

home in Woodstock, NY, suffering injuries to his neck vertebrae and a

concussion. Details of the accident remain elusive — he was reportedly

in critical condition for a week and had amnesia — and some

biographers have questioned its severity, but the event was a pivotal

turning point in his career. After the accident, Dylan became a

recluse, disappearing into his home in Woodstock and raising his family

with his wife, Sara. After a few months, he retreated with the Band to

a rented house, subsequently dubbed Big Pink, in West Saugerties to

record a number of demos. For several months, Dylan and the Band

recorded an enormous amount of material, ranging from old folk,

country, and blues songs to newly written originals. The songs

indicated that Dylan’s songwriting had undergone a metamorphosis,

becoming streamlined and more direct. Similarly, his music had changed,

owing less to traditional rock roll, and demonstrating heavy country,

blues, and traditional folk influences. None of the Big Pink recordings

were intended to be released, but tapes from the sessions were

circulated by Dylan’s music publisher with the intent of generating

cover versions. Copies of these tapes, as well as other songs, were

available on illegal bootleg albums by the end of the ’60s; it was the

first time that bootleg copies of unreleased recordings became widely

circulated. Portions of the tapes were officially released in 1975 as

the double-album The Basement Tapes.

While Dylan was in

seclusion, rock roll had become heavier and artier in the wake of the

psychedelic revolution. When Dylan returned with John Wesley Harding in

December of 1967, its quiet, country ambience was a surprise to the

general public, but it was a significant hit, peaking at number two in

the U.S. and number one in the U.K. Furthermore, the record arguably

became the first significant country-rock record to be released,

setting the stage for efforts by the Byrds and the Flying Burrito

Brothers later in 1969. Dylan followed his country inclinations on his

next album, 1969’s Nashville Skyline, which was recorded in Nashville

with several of the country industry’s top session men. While the album

was a hit, spawning the Top Ten single “Lay Lady Lay,” it was

criticized in some quarters for uneven material. The mixed reception

was the beginning of a full-blown backlash that arrived with the

double-album Self Portrait. Released early in June of 1970, the album

was a hodgepodge of covers, live tracks, re-interpretations, and new

songs greeted with negative reviews from all quarters of the press.

Dylan followed the album quickly with New Morning, which was hailed as

a comeback.

Following the release of New Morning, Dylan began to

wander restlessly. In 1969 or 1970, he moved back to Greenwich Village,

published -Tarantula for the first time in November of 1970, and

performed at ~the Concert for Bangladesh. During 1972, he began his

acting career by playing Alias in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy

the Kid, which was released in 1973. He also wrote the soundtrack for

the film, which featured “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” his biggest hit

since “Lay Lady Lay.” The Pat Garrett soundtrack was the final record

released under his Columbia contract before he moved to David Geffen’s

fledgling Asylum Records. As retaliation, Columbia assembled Dylan, a

collection of Self Portrait outtakes, for release at the end of 1973.

Dylan only recorded two albums — including 1974’s Planet Waves,

coincidentally his first number one album — before he moved back to

Columbia. the Band supported Dylan on Planet Waves and its accompanying

tour, which became the most successful tour in rock roll history; it

was captured on 1974’s double-live album Before the Flood.

Dylan’s

1974 tour was the beginning of a comeback culminated by 1975’s Blood on

the Tracks. Largely inspired by the disintegration of his marriage,

Blood on the Tracks was hailed as a return to form by critics and it

became his second number one album. After jamming with folkies in

Greenwich Village, Dylan decided to launch a gigantic tour, loosely

based on traveling medicine shows. Lining up an extensive list of

supporting musicians — including Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Rambling

Jack Elliott, Arlo Guthrie, Mick Ronson, Roger McGuinn, and poet Allen

Ginsberg — Dylan dubbed the tour ~the Rolling Thunder Revue and set

out on the road in the fall of 1975. For the next year, ~the Rolling

Thunder Revue toured on and off, with Dylan filming many of the

concerts for a future film. During the tour, Desire was released to

considerable acclaim and success, spending five weeks on the top of the

charts. Throughout ~the Rolling Thunder Revue, Dylan showcased

“Hurricane,” a protest song he had written about boxer Rubin Carter,

who had been unjustly imprisoned for murder. The live album Hard Rain

was released at the end of the tour. Dylan released Renaldo and Clara,

a four-hour film based on the ~Rolling Thunder tour, to poor reviews in

early 1978.

Early in 1978, Dylan set out on another extensive

tour, this time backed by a band that resembled a Las Vegas lounge

band. The group was featured on the 1978 album Street Legal and the

1979 live album At Budokan. At the conclusion of the tour in late 1978,

Dylan announced that he was a born-again Christian, and he launched a

series of Christian albums that following summer with Slow Train

Coming. Though the reviews were mixed, the album was a success, peaking

at number three and going platinum. His supporting tour for Slow Train

Coming featured only his new religious material, much to the bafflement

of his long-term fans. Two other religious albums — Saved (1980) and

Shot of Love (1981) — followed, both to poor reviews. In 1982, Dylan

traveled to Israel, sparking rumors that his conversion to Christianity

was short-lived. He returned to secular recording with 1983’s Infidels,

which was greeted with favorable reviews.

Dylan returned to

performing in 1984, releasing the live album Real Live at the end of

the year. Empire Burlesque followed in 1985, but its odd mix of dance

tracks and rock roll won few fans. However, the five-album/triple-disc

retrospective box set Biograph appeared that same year to great

acclaim. In 1986, Dylan hit the road with Tom Petty the Heartbreakers

for a successful and acclaimed tour, but his album that year, Knocked

Out Loaded, was received poorly. The following year, he toured with the

Grateful Dead as his backing band; two years later, the souvenir album

Dylan the Dead appeared.

In 1988, Dylan embarked on what became

known as “The Never-Ending Tour” — a constant stream of shows that ran

on and off into the late ’90s. That same year, he released Down in the

Groove, an album largely comprised of covers. The Never-Ending Tour

received far stronger reviews than Down in the Groove, but 1989’s Oh

Mercy was his most acclaimed album since 1974’s Blood on the Tracks.

However, his 1990 follow-up, Under the Red Sky, was received poorly,

especially when compared to the enthusiastic reception for the 1991 box

set The Bootleg Series, Vols. 1-3 (Rare Unreleased), a collection of

previously unreleased outtakes and rarities.

For the remainder of

the ’90s, Dylan divided his time between live concerts and painting. In

1992, he returned to recording with Good As I Been to You, an acoustic

collection of traditional folk songs. It was followed in 1993 by

another folk album, World Gone Wrong, which won the Grammy for Best

Traditional Folk Album. After the release of World Gone Wrong, Dylan

released a greatest-hits album and a live record.

Dylan released

Time Out of Mind, his first album of original material in seven years,

in the fall of 1997. Time Out of Mind received his strongest reviews in

years and unexpectedly debuted in the Top Ten. Its success sparked a

revival of interest in Dylan — he appeared on the cover of Newsweek

and his concerts became sell-outs. Early in 1998, Time Out of Mind

received three Grammy Awards — Album of the Year, Best Contemporary

Folk Album and Best Male Rock Vocal. ~ Stephen Thomas Erlewine, All

Music Guide