Descrizione

PREMESSA: LA SUPERIORITA’ DELLA MUSICA SU VINILE E’ ANCOR OGGI SANCITA, NOTORIA ED EVIDENTE. NON TANTO DA UN PUNTO DI VISTA DI RESA, QUALITA’ E PULIZIA DEL SUONO, TANTOMENO DA QUELLO DEL RIMPIANTO RETROSPETTIVO E NOSTALGICO , MA SOPRATTUTTO DA QUELLO PIU’ PALPABILE ED INOPPUGNABILE DELL’ ESSENZA, DELL’ ANIMA E DELLA SUBLIMAZIONE CREATIVA. IL DISCO IN VINILE HA PULSAZIONE ARTISTICA, PASSIONE ARMONICA E SPLENDORE GRAFICO , E’ PIACEVOLE DA OSSERVARE E DA TENERE IN MANO, RISPLENDE, PROFUMA E VIBRA DI VITA, DI EMOZIONE E DI SENSIBILITA’. E’ TUTTO QUELLO CHE NON E’ E NON POTRA’ MAI ESSERE IL CD, CHE AL CONTRARIO E’ SOLO UN OGGETTO MERAMENTE COMMERCIALE, POVERO, ARIDO, CINICO, STERILE ED ORWELLIANO, UNA DEGENERAZIONE INDUSTRIALE SCHIZOFRENICA E NECROFILA, LA DESOLANTE SOLUZIONE FINALE DELL’ AVIDITA’ DEL MERCATO E DELL’ ARROGANZA DEI DISCOGRAFICI .

BOB DYLAN

the freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Disco LP 33 giri , CBS , Cbs mono 62193 , mono, 1966, italia

CONDIZIONI MOLTO BUONE, vinyl vg- ( some light scars in vinyl surfaces / lievi segni sulla superficie dei 2 lati del vinile , track B1 lightly damaged

skips in two points at the beginning / la traccia 1 del lato B è

leggermente rovinata in avvio salta in un paio di punti), cover vg+

How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man? One of

the most famous lines in music history opens this album and it sets the

mood immediately. This album is kind of scary in the sense nearly every

song is a classic and if you’d re-titled it “The Essential Bob Dylan”

or “Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits” you probably wouldn’t get much argument.

From the sad romantic songs Girl From the North Country and Don’t Think

Twice, It’s Al; Right to the political Masters of War, Oxford Town to

the comic Talking World War III Blues and all the way to the poetic

Blowin’ in the Wind. This albums shows Dylan as the brilliant lyricist

he was that wasn’t as easy to see on his debut.

This album is probably one of the greatest folk albums ever recorded,

it’s topical as it is romantic and always poetic and real. Bob Dylan

shows himself a much more comfortable folk artists here and a much much

more powerful musician.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (traducibile come Bob Dylan a ruota libera) è il titolo di un album pubblicato da Bob Dylan nel maggio del 1963; è il secondo album ufficiale (il primo con composizioni interamente sue) dell’autore di Duluth dopo il disco d’esordio che portava il suo nome (Bob Dylan, del 1962, composto da cover di brani traditional del folk statunitense).

Oltre a Bob Dylan alla voce, chitarra e armonica, sono presenti come “session man” in Corrina, Corrina (l’unico brano non acustico) R.Wellstood al pianoforte, Bruce Langhorne e G.Barnes alla chitarra elettrica, A.Davis al basso e H.Lovelle alla batteria.

Registrato a New York,

fu prodotto da John Hammond; riporta sulla contro-copertina note con

descrizione dei brani e presentazione del compositore e cantante

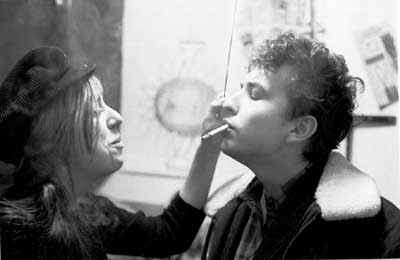

scritte da Nat Hentoff. La foto di copertina ritrae invece un giovane

Dylan a passeggio sottobraccio con la allora fidanzata Suze Rotolo in una strada innevata di New York, scattata l’inverno precedente, al momento del suo arrivo a New York dall’Iron Range del Minnesota.

Il brano dell’album destinato a restare nella storia della musica rock – e a lanciare su scala planetaria il giovane Dylan – fu Blowin’ in the Wind,

che diverrà da allora la canzone di protesta per eccellenza e al tempo

stesso una vera e propria bandiera del pacifismo, per i versi dal

contenuto universale e senza tempo.

L’album comprende tra gli altri motivi anche A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, monito esplicito espresso senza mezzi termini sulle conseguenze di un possibile conflitto nucleare.

Tutte le canzoni di questo album sono degne di memoria, ma

soffermarvici sarebbe troppo lungo e toglierebbe il gusto di ascoltare

e carpire i messaggi direttamente dalla musica e dall’espressiva voce

di Dylan.

Altri brani degni di essere ricordati sono Masters of War, brano che si scaglia contro i “signori della guerra” , vale a dire i fabbricanti di armi, anch’essa diventata quasi un inno per i pacifisti, soprattutto negli anni in cui il conflitto in Vietnam era alle porte.

Infine Talkin’ World War III Blues, acido talkin’ blues (blues parlato, quasi antesignano dei successivi rap) su una possibile nonché temuta terza guerra mondiale.

In conclusione, per molti cultori del fenomeno Dylan, l’album Freewheelin’ può considerarsi come una pietra miliare della cosiddetta canzone d’autore.

Etichetta: Cbs

Catalogo: 62193

Data di pubblicazione: 1966

Matrici: CBS 62193 = 1L / CBS 62193 = 2L

Data Matrici : 7/10/66

- Supporto:vinile 33 giri

- Tipo audio: mono

- Dimensioni: 30 cm.

- Facciate: 2

- Laminated front sleeve / copertina frontale laminata, orange label, poly inner sleeve

Track listing

All songs by Bob Dylan, except where noted

Side one

- “Blowin’ in the Wind” – 2:48

- “Girl from the North Country” – 3:22

- “Masters of War” – 4:34

- “Down the Highway” – 3:27

- “Bob Dylan’s Blues” – 2:23

- “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” – 6:55

Side two

- “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” – 3:40

- “Bob Dylan’s Dream” – 5:03

- “Oxford Town” – 1:50

- “Talkin’ World War III Blues” – 6:28

- “Corrina, Corrina” (Traditional) – 2:44

- “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance” (Dylan, Henry Thomas) – 2:01

- “I Shall Be Free” – 4:49

Personnel

- Bob Dylan – Guitar, Harmonica, Keyboards, Vocals

- Bruce Langhorne – Guitar

- Howard Collins – Guitar

- Leonard Gaskin – Bass guitar

- George Barnes – Bass guitar

- Gene Ramey – Double bass

- Herb Lovelle – Drums

- Dick Wellstood – Piano

- John H. Hammond, Jr. – Producer

- Tom Wilson – Producer

- Nat Hentoff – Liner Notes

- Don Hunstein – Album cover photographer

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is singer-songwriter Bob Dylan‘s second studio album, released in May 1963 by Columbia Records.

Dylan’s debut album, Bob Dylan, had featured just two original songs. Freewheelin’ contained just two covers, the traditional tune “Corrina, Corrina“, and “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance” — which Dylan re-wrote extensively. All the other songs were Dylan originals and the Freewheelin’ album showcased for the first time Dylan’s song-writing talent. The album kicked off with “Blowin’ in the Wind“, which would become one of Dylan’s most celebrated songs. In July 1963, the song became an international hit for folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan reached number 22 in the US

(eventually going platinum), and later became a number 1 hit in the UK

in 1965. It was one of 50 recordings chosen in 2002 by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry.

In 2003, the album was ranked number 97 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Recording sessions

Both critics and the public took little notice of Dylan’s eponymous debut album, Bob Dylan, which sold only 5,000 copies in its first year, just enough to break even. Within Columbia Records some referred to the singer as ‘Hammond’s Folly’ and suggested dropping his contract. Hammond defended Dylan vigorously, and Johnny Cash, who had a strong commercial track record at Columbia, was also a staunch supporter of Dylan. The relatively small company Prestige Records had expressed interest in Dylan, perceiving potential in his songwriting talent. Hammond was committed to making Dylan’s second album a success.

Recording in New York

With Hammond producing, Dylan began work on his second album at Columbia’s Studio A in New York on April 24, 1962. The working title at the time was Bob Dylan’s Blues,

and as late as July, it would remain the working title. Dylan performed

renditions of two traditional folk songs, “Going To New Orleans” and

“Corrina, Corrina”, as well as a cover of the Hank Williams

classic “(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle”. However, much of the session

was dedicated to Dylan’s own compositions, and four of them were

recorded: “Sally Gal”, “The Death of Emmett Till“, “Rambling, Gambling Willie”, and “Talkin’ John Birch Society

Blues”. Dylan’s performances of “John Birch” and “Rambling, Gambling

Willie” were deemed satisfactory, and master takes of both songs were

selected and set aside for the final album.

Dylan returned to Studio A the following day, recording the master take for “Let Me Die In My Footsteps“, which was also set aside for the final album. Dylan then recorded several more originals (“Rocks and Gravel”, “Talking Hava Negiliah

Blues”, “Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues”, and two more

takes of “Sally Gal”), as well as several covers, including the

traditional “Wichita (Going to Louisiana)”, Big Joe Williams‘s “Baby Please Don’t Go”, and Robert Johnson‘s

“Milk Cow’s Calf’s Blues”. Because Dylan’s song-writing talent

developed so rapidly, nothing from the April sessions appeared on Freewheelin’.

In 1991, “Let Me Die in My Footsteps,” “Talking Hava Negiliah Blues,”

and “Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues” were eventually

released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991.

The recording sessions at Studio A would not resume until July 9,

when Dylan recorded several new compositions. The most notable was

“Blowin’ in the Wind”, a song he had already performed live but had yet

to record in the studio. Dylan also recorded “Bob Dylan’s Blues”, “Down

the Highway”, and “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance” and master

takes for these four songs were selected for the album.

Dylan also recorded “Baby, I’m In The Mood For You”, an original

composition, which did not make the final cut for the album; it would

eventually be released in 1985 on the boxed-set retrospective Biograph. Two more outtakes, an original blues number called “Quit Your Low Down Ways” and Texan singer Hally Wood‘s composition, “Worried Blues”, were released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991.

By this time, a manager, Albert Grossman,

was taking an interest in Dylan’s business affairs; Grossman was

involved in music publishing and he persuaded Dylan to take publishing

rights of his songs away from Duchess Music, whom he had signed a

contract with, and assign the publishing to Witmark Music, a division

of Warner’s music publishing operation. Dylan signed a contract with

Witmark on July 13, 1962.

After settling his publishing contract, Dylan returned to Minnesota

at the beginning of August. He stayed in Minneapolis where he met old

friends, including Tony Glover, who recorded another informal ‘session’

with Dylan. On this home recording, Dylan talked about Suze Rotolo,

and Dylan’s expectation that she would return from Italy, where she was

studying art, in September. He then performed an embryonic version of

his new song, “Tomorrow is a Long Time“.

Shortly before September 1, Dylan heard from Suze Rotolo; she told him

that she had postponed her return from Italy indefinitely, which put a

strain on their relationship.

Dylan returned to New York in the fall and performed a number of

live shows where he debuted some new compositions. On September 22,

Dylan appeared for the first time at Carnegie Hall, part of an all-star hootenanny. This show was his first public performance of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall“, a complex and powerful song built upon the question and answer refrain pattern of the traditional British ballad “Lord Randall“, published by Francis Child. One month later, on October 22, President John F. Kennedy appeared on national television to announce the discovery of Soviet missiles on the island of Cuba, initiating the Cuban Missile Crisis. In the sleeve notes on the Freewheelin’ album, Nat Hentoff

would quote Dylan as saying that he wrote “A Hard Rain” in response to

the Cuban Missile Crisis: “Every line in it is actually the start of a

whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough

time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this

one.” In fact, Dylan had written the song more than a month before the

crisis broke.

Albert Grossman became Dylan’s manager in August 1962,

and he quickly clashed with John Hammond. Since Dylan was under

twenty-one when he signed his contract with CBS, Grossman argued that

the contract was invalid and had to be re-negotiated. Instead, Hammond

invited Dylan to his office and persuaded him to sign a ‘reaffirment’ –

agreeing to abide by the original contract. Tension between Grossman and Hammond eventually led to Hammond’s being replaced as Bob Dylan’s producer.

Dylan resumed work on his second album at Columbia’s Studio A on

October 26, where he recorded three songs. Several takes of Dylan’s “Mixed-Up Confusion” and Arthur Crudup‘s “That’s All Right Mama” were deemed unusable,

but a master take of “Corrina, Corrina” was selected for the final

album. An ‘alternate take’ of “Corrina, Corrina” from the same session

would also be selected for a single issued later in the year.

On November 1, Dylan held another session at Studio A where he

performed three songs. Once again, “Mixed-Up Confusion” and “That’s All

Right Mama” were recorded, and once again, the results were deemed

unusable. However, the third song, “Rocks And Gravel,” was deemed

satisfactory, and a master take was selected for the final album.

On November 14, Dylan held another session at Studio A, spending

most of the session recording “Mixed-Up Confusion”. Dylan performed the

song with several studio musicians hired by producer John Hammond;

George Barnes (guitar), Bruce Langhorne (guitar), Dick Wellstood (piano), Gene Ramey (bass), and Herb Lovelle (drums). Although this track never appeared on a Dylan album, it was released as a single on December 14, 1962, and then swiftly withdrawn. What is striking is the rockabilly sound of the backing band. Cameron Crowe described it as “a fascinating look at a folk artist with his mind wandering towards Elvis Presley and Sun Records“.

After completion of “Mixed-Up Confusion”, most of the musicians were

dismissed, but guitarist Langhorne stayed behind, accompanying Dylan on

three more originals (“Ballad of Hollis Brown”, “Kingsport Town”, and

“Whatcha Gonna Do”), but these performances were ultimately rejected;

“Kingsport Town” was later released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991.

Dylan held another session at Studio A three weeks later on December

6. Five songs, all original compositions, were recorded, three of which

were eventually included on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan: “A Hard

Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, “Oxford Town”, and “I Shall Be Free”. All three

master takes were recorded on the first take, with “A Hard Rain’s

A-Gonna Fall” and “Oxford Town” recorded in a single take. Dylan also

made another attempt at “Whatcha Gonna Do” and recorded a new song,

“Hero Blues”, but both songs were ultimately rejected and left

unreleased.

Traveling to England

Twelve days later, Dylan visited England for the first time to appear in a BBC drama, The Madhouse on Castle Street, in which he performed “Blowin’ in the Wind” and two other songs. While in London, Dylan immersed himself in the local folk scene, making contact with Troubadour Club organizer Anthea Joseph and folksingers Martin Carthy

and Bob Davenport. “I ran into some people in England who really knew

those [traditional English] songs,” Dylan recalled in 1984. “Martin

Carthy, another guy named [Bob] Davenport. Martin Carthy’s incredible.

I learned a lot of stuff from Martin.”

Carthy introduced Dylan to two English songs that would prove very important for the Freewheelin’ album. Carthy taught Dylan his arrangement of “Scarborough Fair” which Dylan would use as the basis of his own “Girl from the North Country“. And a 19th century ballad commemorating the death of Sir John Franklin in 1847,”Lord Franklin” gave Dylan the melody for his composition “Bob Dylan’s Dream“.

From England, Dylan traveled to Italy where he joined Albert Grossman who was on tour with his client Odetta. Dylan also hoped to make contact with his girlfriend, Suze Rotolo,

unaware that she had already returned to America. While in Italy, Dylan

finished “Girl from the North Country” as well as an early draft of

another song, “Boots of Spanish Leather”. Dylan then returned to

England where Carthy was given a surprise: “When he came back from

Italy, he’d written “Girl From the North Country”; he came down to the Troubadour and said, ‘Hey, here’s “Scarborough Fair”‘ and he started playing this thing.”

Returning to New York

When Dylan returned to New York in mid-January, he recorded his new composition, “Masters of War” for Broadside

magazine. In the meantime, he got back together with Suze Rotolo, whom

he convinced to move back in to his 4th Street apartment.

Returning from Europe with a batch of new songs, Dylan was

determined to record his new material and re-evaluate the tracks he had

already recorded for his second album. The recording of the new

material paralleled a dramatic move outside the studio: Albert

Grossman’s determination to have John Hammond

replaced as Dylan’s producer at CBS. According to Dylan’s biographer,

Howard Sounes, “The two men could not have been more different. Hammond

was a WASP, so relaxed during recording sessions that he sat with feet up, reading The New Yorker. Grossman was a Jewish businessman with a shady past, hustling to become a millionaire.”

The two men had already clashed badly over Hammond’s persuading Dylan

to ‘reaffirm’ his CBS contract. Grossman was determined to control

every element of Dylan’s career, but he also had a profound belief in

Dylan. Film maker D. A. Pennebaker

commented, “I think Albert was one of the few people that saw Dylan’s

worth very early on, and played it absolutely without equivocation or

any kind of compromise.”

As a result, Columbia paired Dylan with a new producer, a young, African-American named Tom Wilson. At the time, Wilson was more experienced with jazz recording, and he was initially reluctant to work with Dylan.

Wilson recalled: “I didn’t even particularly like folk music. I’d been recording Sun Ra and Coltrane…I

thought folk music was for the dumb guys. [Dylan] played like the dumb

guys, but then these words came out. I was flabbergasted.”

At the April 24th session, Dylan cut five of his newest

compositions: “Girl from the North Country”, “Masters of War”, “Talkin’

World War III Blues”, “Bob Dylan’s Dream”, and “Walls of Red Wing”.

“Walls of Red Wing” was ultimately rejected (it was later released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991), but the other four were included in the revised album sequence.

The final drama of recording Freewheelin’ occurred when Dylan appeared on the The Ed Sullivan Show on May 12, 1963. Dylan had chosen to perform “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues” but was informed by the ‘head of program practices’ at CBS Television that this song was potentially libellous to the John Birch Society.

Rather than comply with TV censorship, Dylan refused to appear.

According to biographer Clinton Heylin. “There remains a common belief

that [Dylan] was forced by Columbia to pull “Talkin’ John Birch Society

Blues” from the album after he walked out on The Ed Sullivan Show” However, the ‘revised’ version of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released on May 27, 1963;

this would have given Columbia Records only two weeks to recut the

album, reprint the record sleeves, and press and package enough copies

of the new version to fill orders. Heylin argues that CBS had probably

forced Dylan to withdraw “John Birch” from the album some weeks

earlier. Dylan responded to this by recording new material on April 24,

and replacing four songs (“John Birch”, “Let Me Die in My Footsteps”,

“Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie”, “Rocks and Gravel”) with his more recent

compositions.

The songs

“Blowin’ In The Wind” is one of Dylan’s most famous compositions. In his sleeve notes for The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, John Bauldie writes that it was Pete Seeger

who first identified the melody of “Blowin’ In The Wind” as Dylan’s

adaptation of the old Negro spiritual “No More Auction Block”.

According to Alan Lomax’s “The Folk Songs of North America“, the

song originated in Canada and was sung by former slaves who fled there

after Britain abolished slavery in 1833. In 1978, Dylan acknowledged

the source when he told journalist Marc Rowland: ‘”Blowin’ In The Wind”

has always been a spiritual. I took it off a song called “No More

Auction Block” — that’s a spiritual and “Blowin’ In The Wind” follows

the same feeling.’ Dylan’s performance of “No More Auction Block” was recorded at the Gaslight Cafe in October 1962, and appeared on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991

Dylan wrote the song early in 1962. It was published for the first time in May 1962, in the sixth issue of Broadside, the magazine founded by Pete Seeger and devoted to topical songs.

“Blowin’ in the Wind” made a huge impact on the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and the song has been described as its ‘anthem’. In Martin Scorsese‘s documentary on Dylan, No Direction Home, Mavis Staples

expressed her astonishment on first hearing the song, and said she

could not understand how a young white man could write something which

captured the frustration and aspirations of black people so powerfully.

Sam Cooke was also deeply impressed by the song and began to perform it in his live act. A version was captured on Cooke’s 1964 album Live At the Copacabana. His more profound response was to write the thoughtful and dignified “A Change Is Gonna Come” which he recorded on January 24, 1964.

“Blowin’ In The Wind” became world famous when it was recorded by Peter, Paul and Mary

who were also managed by Albert Grossman. The single sold a phenomenal

three hundred thousand copies in the first week of release. On July 13, 1963, it reached number two on the Billboard

chart with sales exceeding one million copies. Peter Yarrow says that

when he told Dylan he would make more than $5,000 from the publishing

rights, Dylan was speechless.

Critic Andy Gill wrote: ‘”Blowin’ In The Wind” marked a huge jump in

Dylan’s songwriting. Prior to this, efforts like “The Ballad of Donald

White” and “The Death of Emmett Till” had been fairly simplistic bouts

of reportage songwriting. “Blowin’ In The Wind” was different: for the

first time, Dylan discovered the effectiveness of moving from the

particular to the general. Whereas “The Ballad of Donald White” would

become competely redundant as soon as the eponymous criminal was

executed, a song as vague as “Blowin’ In The Wind” could be applied to

just about any freedom issue. It remains the song with which Dylan’s

name is most inextricably linked, and safeguarded his reputation as a

civil libertarian through any number of changes in style and attitude.”

NPR‘s Tim Riley

describes “Girl from the North Country” as “an

absence-makes-the-heart-grow-confused song, but it’s suffused with a

rueful itch, as though Dylan is singing about someone he may never see

again.” Six years later, Dylan would return to this song on Nashville Skyline, recording it in a duet with country music legend Johnny Cash.

A scathing, anti-war song, “Masters of War” is based on Jean Ritchie‘s arrangement of “Nottamun Town“,

an English riddle song. Written in late 1962 while Dylan was in

England, a number of eyewitnesses (including Martin Carthy and Anthea

Joseph) recall Dylan’s performing the song in folk clubs at the time.

Ritchie would later assert her claim on the song’s arrangement;

according to one Dylan biography, the suit was settled when Ritchie

received $5,000 from Dylan’s lawyers.

Dylan was only 21 years old when he wrote one of his most complex

songs, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, often referred to as “Hard Rain”.

Dylan is said to have premiered “Hard Rain” at the Gaslight Cafe, where

Village performer Peter Blankfield was in attendance. “He put out these

pieces of loose-leaf paper ripped out of a spiral notebook. And he

starts singing [‘Hard Rain’]…He finished singing it, and no one could

say anything. The length of it, the episodic sense of it. Every line

kept building and bursting”.

Dylan performed “Hard Rain” days later at Carnegie Hall on September 22, 1962, as part of a concert organized by Pete Seeger. Seeger was so impressed by “Hard Rain”, he covered it himself in his own set.

Many critics interpreted the lyric ‘hard rain’ as a reference to nuclear fallout, but Dylan resisted the specificity of this interpretation. In a radio interview with Studs Terkel in 1963, Dylan said,

“No, it’s not atomic rain, it’s just a hard rain. It isn’t the

fallout rain. I mean some sort of end that’s just gotta happen… In

the last verse, when I say, ‘the pellets of poison are flooding the

waters’, that means all the lies that people get told on their radios

and in their newspapers.”

Dylan once introduced “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” as “a

statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better…as if

you were talking to yourself.” Written around the same time Suze Rotolo

postponed her stay in Italy, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” is

actually based on a melody taught to Dylan by folksinger Paul Clayton. Riley described the song as “the last word in a long, embittered argument, a paper-thin consolation sung with spite.”

“Bob Dylan’s Dream” was based on the melody of the traditional “Lady Franklin’s Lament“, in which the title character dreams of finding her husband, Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin, alive and well. (Sir John Franklin had vanished on an Arctic expedition in 1845; a stone cairn on King William Island detailing his demise was found in another expedition in 1859.)

“Oxford Town” is Dylan’s sardonic account of events at the University of Mississippi in September 1962. U.S. Air Force veteran James Meredith was the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, located a mile from Oxford, Mississippi and 75 miles (121 km) south of Memphis, Tennessee.

When Meredith first tried to attend classes at the school, a number of

Mississippians pledged to keep the university segregated, including

Mississippi’s own governor Ross Barnett. Ultimately, the University of Mississippi

had to be integrated with the help of U.S. federal troops. Dylan

responded rapidly: his song was published in the November 1962 issue of

Broadside.

“Talkin’ World War III Blues” was a spontaneous composition created in the studio during Dylan’s final session for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

“Corrina, Corrina” was recorded by The Mississippi Sheiks, and by their leader Bo Carter in 1928. The song was covered by artists as diverse as Bob Willis, Big Joe Turner, and Doc Watson. Dylan’s version is notable for the fact that it’s the only track on Freewheelin’ recorded with accompanying musicians. And also, as Todd Harvey points out, Dylan borrows phrases from several Robert Johnson songs: “Stones In My Passway”, “32-20 Blues”, and “Hellhound On My Trail”.

“Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance” is based on “Honey, Won’t You

Allow Me One More Chance?”, a song dating back to the 1890s that was

popularized by Henry Thomas in his 1928 recording. “However, Thomas’s

original provided no more than a song title and a notion”, writes

Heylin, “which Dylan turned into a personal plea to an absent lover to

allow him ‘one more chance to get along with you.’ It is a vocal tour

de force and…showed a Dylan prepared to make light of his own blues

by using the form itself.”

“I Shall Be Free” is a rewrite of Leadbelly‘s “We Shall Be Free”, which was performed by Leadbelly, Sonny Terry, Cisco Houston, and Woody Guthrie.

According to musicologist Todd Harvey, Dylan’s version draws its melody

from the Guthrie recording but omits its signature chorus (“We’ll soon

be free/When the Lord will call us home”). Most of Dylan’s version

describes the singer’s uneasy relationship with women, and also some

striking references to contemporary culture: a phone call from JFK, a

satire on TV advertising, and some prodigious drinking. Placed at the

end of the Freewheelin’ LP, the song provides some welcome levity.

Outtakes

Sheet music for “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues” first appeared in the debut issue of Broadside magazine in late February 1962. Conceived by Pete Seeger and Agnes ‘Sis’ Cunningham, Broadside was a magazine dedicated to publishing contemporary folk songs.

Dylan was introduced to Cunningham through Seeger, and during his first

meeting with Cunningham, Dylan played her the song. A wry but humorous

satire that also worked as a scathing portrayal of right-wing paranoia,

it would be the first of many contributions to Broadside magazine.

“The best of Dylan’s early protest songs,” according to Clinton

Heylin, “‘Let Me Die in My Footsteps’ placed a topical preoccupation –

the threat of nuclear war – inside a universal theme – ‘learning to

live, ‘stead of learning to die.'”

“I was going through some town…and they were making this bomb shelter

right outside of town, one of these sort of Coliseum-type things and

there were construction workers and everything,” Dylan recalled to Nat Hentoff

in 1963. “I was there for about an hour, just looking at them build,

and I just wrote the song in my head back then, but I carried it with

me for two years until I finally wrote it down. As I watched them

building, it struck me sort of funny that they would concentrate so

much on digging a hole underground when there were so many other things

they should do in life. If nothing else, they could look at the sky,

and walk around and live a little bit, instead of doing this immoral

thing.” “Let Me Die in My Footsteps” was also selected for the original

sequence of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, but was eventually replaced with “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”.

It’s unclear whether “Mixed Up Confusion” was ever a serious contender for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,

but it was issued by Columbia as a single-only release during the

Christmas shopping season. Dylan had been an avid fan of rock &

roll ever since his childhood, and “Mixed Up Confusion” was his first

record to recall the early rockabilly recordings of his youth. It was also his first Columbia release to group him with a studio band.

Though it wasn’t recorded for the album, “Tomorrow Is a Long Time”

was written and demo’d in between album sessions. If it wasn’t inspired

by personal events unfolding at the time, it’s arguably a reflection of

them as it’s sung from the point-of-view of a narrator who refuses to

lie down in his bed ‘once again’ until his ‘own true love’ is back and

waiting. Widely considered one of Dylan’s finest love songs, Dylan

eventually released “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” in 1971 on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II, which included a live performance taken from his Town Hall concert on April 12, 1963. Heylin describes the Town Hall performance as “an achingly lovely rendition of his most tender song.”

Earlier in 1971, Rod Stewart would release his own cover of “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” on Every Picture Tells a Story, one of Stewart’s more popular albums. Ironically, Dylan recorded the song in 1970 during the New Morning sessions, with a backing band and singers, and an unlikely uptempo blues arrangement. This version has turned up in bootlegs.

In 1966, Elvis Presley recorded the song for the soundtrack of the film

Spinout: Bob Dylan said this was his favorite cover version of any of

his songs.

Due to Dylan recording material over several months in preparation

for his next album, there was a very large surplus of songs that simply

didn’t make the cut. Several original songs and cover tunes were

recorded. Some he would revisit later, and some of the others would be

released officially on The Bootleg Series. A majority of the

tracks remain officially unreleased, though they are circulating. A

live version of “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues” retitled, “Talkin’

John Birch ‘Paranoid’ Blues” was released on The Bootleg Series, but the studio version has not been released.

These are the known outtakes to the album:

- “Baby, Please Don’t Go” (Later released as part of the “Exclusive Outtakes From No Direction Home“, a three song online sampler EP, which contained outtakes from the soundtrack of the Martin Scorsese Dylan biopic, No Direction Home.)

- “Ballad of Hollis Brown” (unreleased): Dylan re-recorded this for his next album, The Times They Are a-Changin’.

- “The Death of Emmett Till” (unreleased)

- “Going to New Orleans” (unreleased)

- “Hero Blues” (unreleased)

- “(I Heard that) Lonesome Whistle” (Hank Williams, Jimmie Davies) (unreleased)

- “Kingsport Town” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Let Me Die in My Footsteps”: truncated version without the last verse released The Bootleg Series 1-3. The full version is circulating.

- “Milkcow’s Calf Blues” (unreleased)

- “Mixed Up Confusion” (released on Biograph)

- “Quit Your Lowdown Ways” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Sally Gal” (released on No Direction Home: The Bootleg Series Vol. 7)

- “Rambling, Gambling Willie” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Rocks and Gravel” [aka “Solid Road”] (unreleased)

- “Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Talking Hava Negiliah Blues” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Talkin’ John Birch ‘Paranoid’ Blues” (live version released on “The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall“)

- “That’s Alright Mama” (unreleased)

- “The Walls of Redwing” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

- “Watcha Gonna Do” (unreleased)

- “Wichita” (unreleased)

- “Worried Blues” (released on The Bootleg Series 1-3)

A few copies of the original pressing of the LP — with the

subsequently deleted tracks, “Let Me Die In My Footsteps”, “Ramblin’

Gamblin’ Willie”, “Rock and Gravel” and “Talkin’ John Birch Society

Blues” — have turned up over the years, despite Columbia’s supposed

destruction of all copies during the pre-release phase. CBS

did manufacture records with these four songs, but not the

corresponding covers. All known copies that have been found are

contained in the standard cover.

In April, 1992, the first known stereo copy (with the label listing

the four songs) was found at a Greenwich Village thrift store in New

York City. The record was used and it was auctioned via Goldmine magazine

and fetched $12,345.67. It would probably have fetched more if it had

been in mint condition. The story was told in an article in Goldmine’s

“Price Guide to Collectible Record Albums”, 4th edition by Neal Umphred.

Aftermath

Dylan promoted his upcoming album with a number of radio appearances and concert performances. Dylan performed with Joan Baez

at the Monterey Folk Festival, where she joined him in a rendition of

Dylan’s “With God on Our Side” (which would not be recorded until his

next album). The performance was seen as a ringing endorsement from

Baez, but was also the beginning of a romantic relationship.

Later, in July, Dylan appeared at the second Newport Folk Festival. By then, Peter, Paul and Mary had a hit with their own rendition of “Blowin’ in the Wind”, and that weekend, it had reached #2 on Billboard’s pop charts. Baez was also at Newport, and she performed with Dylan twice, once on his set, once on hers.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan had been available since late May, but despite the controversy surrounding Dylan’s cancelled Sullivan

appearance, the album itself did not attract many reviews from the

mainstream press. It sold modestly upon its release, but with Dylan’s

appearance at Newport, Baez’s endorsement, and popular covers of his

own songs from both Baez, Odetta and Peter, Paul and Mary,

sales began to rise as word of mouth spread. Dylan’s friend Bob Fass

recalls that after Newport, Dylan told him that “suddenly I just can’t

walk around without a disguise. I used to walk around and go wherever I

wanted. But now it’s gotten very weird. People follow me into the men’s

room just so they can say that they saw me pee.”

By September, the album finally entered Billboard’s album charts. The highest position it reached was number 22. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan would be remembered as the album that first brought Dylan’s talent to a wide audience.

In March 2000, Van Morrison told the Irish rock magazine Hot Press about the impact that Freewheelin’

made on him: “I think I heard it in a record shop in Smith Street. And

I just thought it was incredible that this guy’s not singing about

‘moon in June’ and he’s getting away with it. That’s what I thought at

the time. The subject matter wasn’t pop songs, ya know, and I thought

this kind of opens the whole thing up…Dylan put it into the

mainstream that this could be done.”

The Beatles were also impressed. George Harrison

remembered, “We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the

song lyrics and just the attitude — it was incredibly original and

wonderful.”

Cover art

The album cover features a photograph of Dylan with his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo. The photo was taken by CBS staff photographer Don Hunstein at the corner of Jones Street and West 4th Street in Greenwich Village, New York City—just a few yards away from the apartment where the couple lived at the time. The circumstances behind the shoot are described by Rotolo in A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties.

In popular culture

- In the film Vanilla Sky,

the protagonist, David, walks with Sofia down a street purposely in the

manner of the album cover and even with identical cars. - Mudhoney‘s Mark Arm has released a solo single named under a similar title, The Freewheelin’ Mark Arm.

- In an easter egg in a Homestar Runner cartoon, Eh! Steve appears on this very CD cover as “The Freewheelin’ Eh! Steve”.

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,

the record that firmly established Dylan as an unparalleled songwriter,

one of considerable skill, imagination, and vision. At the time, folk

had been quite popular on college campuses and bohemian circles, making

headway onto the pop charts in diluted form, and while there certainly

were a number of gifted songwriters, nobody had transcended the scene

as Dylan did with this record. There are a couple (very good) covers,

with “Corrina Corrina” and “Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance,” but

they pale with the originals here. At the time, the social protests

received the most attention, and deservedly so, since “Blowin’ in the

Wind,” “Masters of War,” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” weren’t just

specific in their targets; they were gracefully executed and even

melodic. Although they’ve proven resilient throughout the years, if

that’s all Freewheelin’ had to offer, it wouldn’t have had its

seismic impact, but this also revealed a songwriter who could turn out

whimsy (“Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”), gorgeous love songs

(“Girl From the North Country”), and cheerfully absurdist humor (“Bob

Dylan’s Blues,” “Bob Dylan’s Dream”) with equal skill. This is rich,

imaginative music, capturing the sound and spirit of America as much as

that of Louis Armstrong, Hank Williams, or Elvis Presley. Dylan, in many ways, recorded music that equaled this, but he never topped it.

Of all the precipitously emergent singers of folk songs in the

continuing renascence of that self-assertive tradition, none has

equaled Bob Dylan singularity of impact. As Harry Jackson, a cowboy

singer and a painter, has exclaimed: “He’s so goddamned real it’s

unbelievable!” The irrepressible reality of Bob Dylan is a compound of

spontaneity, candor, slicing wit and an uncommonly perceptive eye and

ear for the way many of us constrict our capacity for living while a

few of us don’t.

Not yet twenty-two at the time of this albums release, Dylan is

growing at a swift, experience-hungry rate. In these performances,

there is already a marked change from his first album (“Bob Dylan,”

Columbia CL 1779/CS 8579), and there will surely be many further

dimensions of Dylan to come. What makes this collection particularly

arresting that it consists in large part of Dylan’s own compositions

The resurgence of topical folk songs has become a pervasive part of the

folk movement among city singers, but few of the young bards so far

have demonstrated a knowledge of the difference between

well-intentioned pamphleteering and the creation of a valid musical

experience. Dylan has. As the highly critical editors of “Little Sandy

Review” have noted, “…right now, he is certainly our finest

contemporary folk song writer. Nobody else really even comes close.”

The details of Dylan’s biography were summarized in the notes to his

first Columbia album; but to recapitulate briefly, he was born on May

24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota. His experience with adjusting himself

to new sights and sounds started early. During his first nineteen

years, he lived in Gallup, New Mexico: Cheyenne, South Dakota; Sioux

Falls, South Dakota; Phillipsburg, Kansas; Hibbing, Minnesota (where he

was graduated from high school), and Minneapolis (where he spent a

restless six months at the University of Minnesota).

“Everywhere he went,” Gil Turner wrote in his article on Dylan in

“Sing Out,” “his ears were wide open for the music around him. He

listened to the blues singers, cowboy singers, pop singers and others

— soaking up music and styles with an uncanny memory and facility for

assimilation. Gradually, his own preferences developed and became more

, the strongest areas being Negro blues and county music. Among the

musicians and singers who influenced him were Hank Williams, Muddy

Waters, Jelly Roll Morton, Leadbelly, Mance Lipscomb and Big Joe

Williams.” And, above all others, Woody Guthrie. At ten he was playing

guitar, and by the age of fifteen, Dylan had taught himself piano,

harmonica and autoharp.

In February 1961, Dylan came East, primarily to visit Woody Guthrie

at the Greystone Hospital in New Jersey. The visits have continued, and

Guthrie has expressed approval of Dylan’s first album, being

particularly fond of the “Song to Woody” in it. By September of 1961,

Dylan’s singing in Greenwich Village, especially at Gerde’s Folk City,

had ignited a nucleus of singers and a few critics (notably Bob Shelton

of the “New York Times”) into exuberant appreciation of his work. Since

then, Dylan has inexorably increased the scope of his American

audiences while also performing briefly in London and Rome.

The first of Dylan’s songs in this set is “Blowin’ in the Wind.” In

1962, Dylan said of the song’s background: “I still say that some of

the biggest criminals are those that turn their heads away when they

see wrong and they know it’s wrong. I’m only 21 years old and I know

that there’s been too many wars…You people over 21 should know

better.” All that he prefers to add by way of commentary now is: “The

first way to answer these questions in the song is by asking them. But

lots of people have to first find the wind.” On this track, and except

when otherwise noted, Dylan is heard alone-accompanying himself on

guitar and harmonica.

“Girl From the North Country” was first conceived by Bob Dylan about

three years before he finally wrote it down in December 1962. “That

often happens,” he explains. “I carry a song in my head for a long time

and then it comes bursting out.” The song-and Dylan’s

performance-reflect his particular kind of lyricism. The mood is a

fusion of yearning, poignancy and simple appreciation of a beautiful

girl. Dylan illuminates all these corners of his vision, but

simultaneously retains his bristling sense of self. He’s not about to

go begging anything from this girl up north.

“Masters of War” startles Dylan himself. “I’ve never really written

anything like that before,” he recalls. “I don’t sing songs which hope

people will die, but I couldn’t help it in this one. The song is a sort

of striking out, a reaction to the last straw, a feeling of what can

you do?” The rage (which is as much anguish as it is anger) is a away

of catharsis, a way of getting temporary relief from the heavy feeling

of impotence that affects many who cannot understand a civilization

which juggles it’s own means for oblivion and calls that performance an

act toward peace.

“Down the Highway” is a distillation of Dylan’s feeling about the

blues. “The way I think about the blues,” he says, “comes from what I

learned from Big Joe Williams. The blues is more than something to sit

home and arrange. What made the real blues singers so great is that

they were able to state all the problems they had; but at the same

time, they were standing outside them and could look at them. And in

that way, they had them beat. What’s depressing today is that many

young singers are trying to get inside the blues, forgetting that those

older singers used them to get outside their troubles.”

“Bob Dylan’s Blues” was composed spontaneously. It’s one of what he

calls his “really off-the-cuff songs. I start with an idea, and then I

feel what follows. Best way I can describe this one is that it’s sort

of like walking by a side street. You gaze in and walk on.”

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” represents to Dylan a maturation of his

feelings on this subject since the earlier and almost as powerful “Let

Me Die in My Footsteps,” which is not included here but which was

released as a single record by Columbia. Unlike most of his

song-writing contemporaries among city singers, Dylan doesn’t simply

make a polemical point in his compositions. As in this sing about the

psychopathology of peace-through-balance-of-terror, Dylan’s images are

multiply (and sometimes horrifyingly) evocative. As a result, by

transmuting his fierce convictions into what can only be called art,

Dylan reaches basic emotions which few political statements or

extrapolations of statistics have so far been able to touch. Whether a

song or a singer can then convert others is something else again.

“Hard Rain,” adds Dylan, “is a desperate kind of song.” It was

written during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 when those who

allowed themselves to think of the impossible results of the

Kennedy-Khrushchev confrontation were chilled by the imminence of

oblivion. “Every line in it,” says Dylan, “is actually the start of a

whole song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time

alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

Dylan treats “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” differently from most

city singers . “A lot of people,” he says, “make it sort of a love

song-slow and easy-going. But it isn’t a love song. It’s a statement

that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better. It’s as if you

were talking to yourself. It’s a hard song to sing. I can sing it

sometimes, but I ain’t that good yet. I don’t carry myself yet the way

that Big Joe Williams, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and Lightnin’ Hopkins

have carried themselves. I hope to be able to someday, but they’re

older people. I sometimes am able to do it, but it happens, when it

happens, unconsciously. You see, in time, with those old singers, music

was a tool-a way to live more, a way to make themselves feel better at

certain points. As for me, I can make myself feel better some times,

but at other times, it’s still hard to go to sleep at night.” Dylan’s

accompaniment on this track includes Bruce Langhorne (guitar), George

Barnes (bass guitar), Dick Wellstood (piano), Gene Ramey (bass) and

Herb Lovelle (drums).

“Bob Dylan’s Dream” is another of his songs which was transported

for a time in his mind before being written down. It was initially set

off after all-night conversation between Dylan and Oscar Brown, Jr., in

Greenwich Village. “Oscar,” says Dylan, “is a groovy guy and the idea

of this came from what we were talking about.” The song slumbered,

however, until Dylan went to England in the winter of 1962. There he

heard a singer (whose name he recalls as Martin Carthy) perform “Lord

Franklin,” and that old melody found a new adapted home in “Bob Dylan’s

Dream.” The song is a fond looking back at the easy camaraderie and

idealism of the young when they are young. There is also in the “Dream”

a wry but sad requiem for the friendships that have evaporated as

different routes, geographical and otherwise, are taken.

Of “Oxford Town,” Dylan notes with laughter that “it’s a banjo tune

I play on the guitar.” Otherwise, this account of the ordeal of James

Meredith speaks grimly for itself.

“Talking World War III Blues” was about half formulated beforehand

and half improvised at the recording session itself. The “talking

blues” form is tempting to many young singers because it seems so

pliable and yet so simple. However, the simpler a form, the more

revealing it is of the essence of the performer. There’s no place to

hide in the talking blues. Because Bob Dylan is so hugely and

quixotically himself, he is able to fill all the space the talking

blues affords with unmistakable originality. In this piece, for

example, he has singularly distilled the way we all wish away our end,

thermonuclear or “natural.” Or at least, the way we try to.

“Corrina, Corrina” has been considerably changed by Dylan. “I’m not

one of those guys who goes around changing songs just for the sake of

changing them. But I’d never heard Corrina, Corrina exactly the way it

first was, so that this version is the way it came out of me.” As he

indicates here, Dylan can be tender without being sentimental and his

lyricism is laced with unabashed passion. The accompaniment is Dick

Wellstood (piano), Howie Collins (guitar), Bruce Langhorne (guitar),

Leonard Gaskin (bass) and Herb Lovelle (drums).

“Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance” was first heard by Dylan from

a recording by a now-dead Texas blues singer. Dylan can only remember

that his first name was Henry. “What especially stayed with me,” says

Dylan, “was the plea in the title.” Here Dylan distills the buoyant

expectancy of the love search.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Dylan isn’t limited to one or two

ways of feeling his music. He can be poignant and mocking, angry and

exultant, reflective and whoopingly joyful. The final “I Shall Be Free”

is another of Dylan’s off-the-cuff songs in which he demonstrates the

vividness, unpredictability and cutting edge of his wit.

This album, in sum, is the protean Bob Dylan as of the time of the

recording. By the next recording, there will be more new songs and

insights and experiences. Dylan can’t stop searching and looking and

reflecting upon what he sees and hears. “Anything I can sing,” he

observes, “I call a song. Anything I can’t sing, I call a poem.

Anything I can’t sing or anything that’s too long to be a poem, I call

a novel. But my novels don’t have the usual story lines. They’re about

my feelings at a certain place at a certain time.” In addition to his

singing and song writing, Dylan is working on three “novels.” One is

about the week before he came to New York and his initial week in that

city. Another is about South Dakota people he knew. And the third is

about New York and a trip from New York to New Orleans.

Throughout everything he writes and sings, there is the surge of a

young man looking into as many diverse scenes and people as he can find

(“Every once in a while I got to ramble around”) and of a man looking

into himself. “The most important thing I know I learned from Woody

Guthrie,” says Dylan. “I’m my own person. I’ve got basic common

rights-whether I’m here in this country or any other place. I’ll never

finish saying everything I feel, but I’ll be doing my part to make some

sense out of the way we’re living, and not living, now. All I’m doing

is saying what’s on my mind the best way I know how. And whatever else

you say about me, everything I do and sing and write comes out of me.”

It is this continuing explosion of a total individual, a young man

growing free rather than absurd, that makes Bob Dylan so powerful and

so personal and so important a singer. As you can hear in these

performances.

— Nat Hentoff

chitarra che cercava di emulare le gesta di Guthrie e Hank e che aveva

l’aria un po’ alla Jimmy Dean e un po’ alla Robert Johnson era arrivato

a New York…

Maggio 1963: La Columbia pubblica “The Freewheelin’

Bob Dylan”, il disco che scatenerà un vero e proprio terremoto nella

storia della musica. Solamente un anno prima era uscito l’album

d’esordio di Dylan, un disco che dimostrava in modo indiscutibile che

quel ragazzo si portava il folk nelle tasche e il blues nella testa, ma

con questa seconda prova Dylan mostra di portarsi appresso anche

un’altra cosa e questa volta nel cuore: La Poesia.

Il folk, il

country, il blues sono dei generi che hanno sempre avuto dei testi

molto belli, ma mai fino a questo momento avevano avuto una tale forza simbolica e visionaria come quella che gli donò Dylan.

Dylan

compone, suona e canta brani di una bellezza sconvolgente, dimostra di

aver carpito il segreto di quei giganti che lo hanno preceduto ed è

questo il motivo per cui tutto in questo disco è perfezione!

Che dire delle canzoni quando ormai si è già detto tutto? Chi

conosce la musica conosce bene queste canzoni che raccontano di ragazze

del nord che vivono dove i venti battono forti alle frontiere,

d’autostrade contorte, d’amori finiti, lasciati o peggio e ancora sogni

brucianti d’infanzia e ubriachi che sognano la libertà… Canzoni che

prima commuovono e divertono, poi denunciano: la guerra, il razzismo,

l’ingiustizia… Poi si sprofonda nella visione della apocalisse di A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall, in cui Dylan canta forse la frase più illuminante sul suo misterioso personaggio: “ ..saprò bene la mia canzone prima di mettermi a cantare“. La risposta soffia nel vento… bè quella risposta è la Musica.

Nulla fu più lo stesso.

A Freewheelin’ Time

Suze Rotolo:

she was the woman walking beside Bob Dylan on the album cover for The

Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan — was Bob Dylan’s girlfriend in the early 1960s.

She’s an artist, and a teacher at the Parsons School of Design in New

York.

And she’s written about her relationship with Dylan in a

memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the

Sixties.

In “Talkin’ World War III Blues” Dylan offers a humorous look at

nuclear war. The song is supposed to be a dream of Dylan’s where he is

walking around after a thermonuclear war. Bob Dylan is telling dream to

a psychiatrist, Dylan describes all sorts of funny scenes as he wanders

around a town. It may seem odd that one could joke about something so

frightening. I think it may be a way for Dylan to deal with his fears

during the cold war, by trivializing the what situation would be like

after a nuclear war. It is sort of scary looking at this from a stand

point of not being alive during the cold war. I can hardly imagine

dealing with the fear of a thermonuclear war causing a scene like the

one Dylan portrays. Even though Dylan makes fun of the situation, the

reality is that it must have been a very scary time.

«”Talking World War III Blues” was about half formulated beforehand and

half improvised at the recording session tself. The “talking blues”

form is tempting to many young singers because it seems so pliable and

yet so simple. However, the simpler a form, the more revealing it is of

the essence of the performer. There’s no place to hide in the talking

blues. Because Bob Dylan is so hugely and quixotically himself, he is

able to fill all the space the talking blues affords with unmistakable

originality. In this piece, for example, he has singularly distilled

the way we all wish away our end, thermonuclear or “natural.” Or at

least, the way we try to.»